Paper #1 PAB Post #1

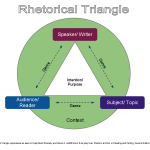

Image of rhetorical triangle reproduced by Katherine Maloney, as seen in Roskelly & Jolliffe’s text Everyday Use: Rhetoric at Work in Reading and Writing, 2nd Edition. 2009, 16.

Faigley, Lester. “Competing Theories of Process: A Critique and a Proposal.” College English, 48.6 (October 1986) 527-542. Print.

Like scholars writing about a so-called crisis in English Studies, Faigley explores the contemporary conflict heating up in the field of writing and composition studies in the 1980’s. He analyzes the theories forwarded about how to align the pedagogies of rhetoric and composition studies, and bring coherence to an otherwise incoherent field that cannot decide on its own processes. His argument is that a historical understanding of the evolution of writing studies is necessary for the writing instructor and for new lines of integrative research in order to present an axiology that values process, rhetoric, expressivism, and contextual realities, and other concerns in the field. He analyzes scholars such as Peter Elbow, Stanley Fish, James Berlin, David Barthlomae, Maxine Hairston, Patricia Bizzell and Linda Flowers, among others.

Faigley argues for four areas of research necessary to incorporate a “social view of writing,” that is “characterized by the traditions from which they emerge: poststructuralist theories of language, the sociology of science, ethnography, and Marxism” (535). These four points of consideration will lead to an aligned definition of the writing process and what that process entails. Up until the time of his writing, competing theories and theorist have torn asunder any common ground in writing studies, much like the larger debates that roil the field of English Studies. Faigley identifies three distinct factions in the writing process field: the expressivists, who emphasize individual (or “authentic”) voice, the cognitivists, who stress process and procedure, and what he terms the “social view,” which “contends processes of writing are social in character instead of originating within individual writers” (528).

As a microcosmic view of a sub-discipline within English Studies, writing studies also suffers its share of dissent and opposing interests and perspectives, as well as the major question of whether writing studies should have disciplinary status. While Faigley is writing in 1986, his analysis of the problems that writing studies face is comparable to McComiskey and Fulkerson’s modern day discourse on the conflict within English Studies as a discipline. Like McComiskey, Faigley argues for an integrative approach that incorporates but does not privilege one pedagogical approach over another, but instead finds areas of commonality that can resolve the disputations between theorists.

Ultimately, Faigley is arguing that a “historical awareness would allow us to reinterpret and integrate each of the theoretical perspectives…” (537), and move writing studies towards theoretical synthesis, rather than competing views. He concludes that debates among scholars distract us from questioning why American universities and colleges teach writing composition, why writing courses are offered even after the “’literacy crisis’ of the seventies has abated,” and why writing courses are taught by nontenured instructors and graduate students (539). Faigley argues that answering these questions moves the discussion to the more relevant recognition that writing processes are contextual, community-based, and progressive; not just one of these things, but all at the same time.